Fresh light on Van Gogh

Why do some colours in Vincent van Gogh's paintings gradually change, and what can be done about it? That is what the Van Gogh Museum is trying to find out together with ASML and various scientific institutions. To store, share and process the data, they collaborate in SURF's Research Drive and Research Cloud.

Key facts

Who: Marco Roling and Michiel Goosen

Function: datasteward; head of collection-information and library

Organisation: Van Gogh Museum

Service: Research Drive and Research Cloud

Challenge: collaboratively store, share and analyse many terabytes of different types of research data

Solution: a shared data environment that is trusted by all parties

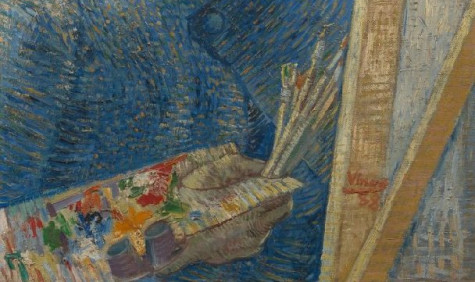

"A pink-grey face with green eyes, ash-coloured hair, wrinkles in the forehead and around the mouth, stiffly woody, a very red beard, quite distraught and sad, but the lips are full, a blue smock of coarse linen and a palette of lemon yellow, vermilion, veronese green, cobalt blue, all colours enfin, except the orange beard, on the palette, the only whole colours however."

This is how Vincent van Gogh described one of his self-portraits to his sister Willemien in June 1888. Everyone knows Van Gogh's bright, vibrant colours. Now, more than a hundred years later, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam is researching the ageing of his paintings. Because light, temperature and humidity affect the condition of a painting.

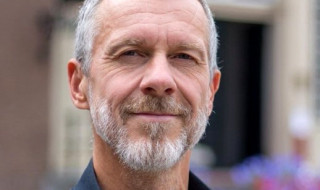

Marco Roling

Art historical, material-technical and natural science research was already being done by the museum itself, but more interdisciplinary research on a larger scale is needed to detect ageing and find the causes and possible measures. Marco Roling, data steward at the Van Gogh Museum, outlines the questions involved: "What kind of paint did Van Gogh use? From which pigments does the colour change and how can we slow down that process?"

The scans provide terabytes of information in some cases

Scans and samples

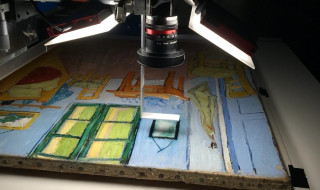

The museum does not have all the necessary equipment and expertise in-house and is therefore collaborating with the tech company ASML, the University of Amsterdam and the Cultural Heritage Agency, among others. Using advanced equipment, partly developed by ASML, the paintings are scanned at various wavelengths: with X-rays, infrared cameras and UV light. This maps out the different layers of paint. Samples of the paint are also taken to see what materials it consists of.

During a pilot project launched by the Van Gogh Museum and ASML in 2017, an instrument was designed to take accurate colour measurements

"The National Cultural Heritage Agency has a big lab over there opposite the Rijksmuseum," Roling points through the window. "That's where the chemical elements of paint are analysed. The techniques are getting better and better. You used to need a sample of a millimetre wide; now we can use a tiny paint sample that you can't even see with the naked eye."

Michiel Goosen (photo Petra Dorenstouter)

"From the written sources in our archives, we know a lot about the painter," says Michiel Goosen, who is Head of Collection Information and Library at the Van Gogh Museum. "He described which paints he used and that he saw some types discolouring himself. So we know that certain dyes are apparently less stable. Combining this knowledge with other fields of science provides interesting new perspectives."

Shared and trusted data environment

'Pear tree in bloom' is one of the works analysed in this project (credits: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation))

The scans yield terabytes of information in some cases. The researchers also collect many different types of data. Data management is therefore becoming increasingly important. "You want scientific research to be reproducible," says Goosen. "That's why you have to record everything: with which device was this measured, is it a text file, a picture file or something else?"

So there was a need for a shared data environment that was trusted by all parties, adds data steward Roling. "We therefore started using SURF Research Drive for storing and sharing the data and software, and recently SURF Research Cloud for analysing it. We didn't want to overburden our own automation department with this, as it is an experimental project."

"SURF has experience with scientific data and collaboration between different parties. It is a neutral party with no commercial interest and good support. I am also happy with the user group meetings, where you exchange experiences with SURF and other users."

Transparent dataflow: from scan to interpretation

Besides his work in IT, Roling is also an autonomous artist. Perhaps that is why he approaches his IT challenges in a creative way. "When you start using Research Drive, it's actually an empty environment with folders. To organise that neatly, I used the metaphor of an Amsterdam canal house: there is a door, a hall, an attic, and there are several rooms."

"To clearly structure the Research Drive environment for all users, I use the metaphor of an Amsterdam canal house"

Each space has a specific function and not everyone has access to the same areas. "If you want to deliver a package of data, basically like a parcel deliverer, you put it down in the hall. Then the data steward takes the package to the back room to unpack it. I actually gave the folders the names of these rooms. That way, the whole flow is transparent: from scan to interpretation."

A measurement with sensors has already shown that the amount of visitors standing in front of the artworks, which are almost 6,000 a day, does not have much influence. Light and humidity all the more. Those factors are therefore strictly regulated in the exhibition halls. It's a huge dilemma for the museum: you want everyone to be able to enjoy Van Gogh's art, but by exhibiting the works, they do age. Hopefully, thanks to this research, we will be able to enjoy Van Gogh responsibly for a long time to come.

Text: Josje Spinhoven